The Directionalizer

The next morning Fozzie and I set out at 8:00 a.m.: he to go to work, me to hit as many shrines and temples as a human can hit in a single day.

The Hongans

I walked straight down the street to Higashi (East) Hongan-ji, said to be the lesser of the two Hongan temples. A sign on the grounds gave it the distinction of being largest wooden building in the world, and I enjoyed free rein to walk around since the place was pretty much deserted. I poked my nose inside to look at some of the golden frieze work, but neglected to seek out a rope made of the hair of female devotees, apparently a major feature.

Nishi (West) Hongan-ji, two blocks down, looked exactly like a smaller version of East Hongan-ji. Then I realized that I was only looking at a third of the compound. The massive metal building blocking my view, which I’d thought to be a poorly-placed gymnasium, was actually covering the ongoing restoration of the main hall, scheduled to continue until 2010. Some attendants on the north side of the metal box gave me a flyer showing pictures of a beautiful-looking garden, but when I asked about it they said I couldn’t go in there either. I'm not sure what the point of the place is.

Kinkaku-ji

I headed down to the station and got on a bus to Kinkaku-ji, possibly the single most famous image of Kyoto. Also called The Golden Pavilion, Kinkakui-ji is a gold-plated three-story structure resting in the midst of an immaculate pond dotted with pristine little islands of vivid green. It is also in the middle of nowhere and cut a swath of time out of my day, but I knew I had to see it.

When I finally got out there, an attendant stopped me and pointed to a white board by the entrance. The English translation read:

|

“Kinkakuji is under repairs until April 1. You can not see anything.” |

The whole thing was under a giant, opaque tarp.

I bought a ticket anyway. I’d taken the time to get out there, and I was going to see whatever there was to be seen.

Placid, immaculate pond. Pristine green islands. Cute little stream. Gorgeous three-story golden pavilion completely concealed under a dull green tent. Huzzah.

There were still tour groups going through.

There did remain a certain serene and delicate beauty to it all, even without the central structure, but somehow the big painting stuck into the ground across from the green tent didn’t quite take the place of the real thing. My 2nd year junior high school kids will unfortunately be making the trip in March.

Nijo-jo

I hopped on a bus that was heading to Kawaramachi station with the confidence that, even if it didn’t go anywhere near Nijo Castle, my next stop, I’d still be able to find my way.

I got lucky: the bus made a stop right in front of the castle walls.

Nijo-jo wasn’t particularly noteworthy from the outside, but the extensive interior was neat: it was commissioned 400 years ago by Ieyasu Tokugawa, the first of the Tokugawa shogunate, and he had most of the building fitted with “nightingale floors” that squeak at every step to protect against assassins. Walking around behind a group of tourists, it sounded like a horde of children going back and forth on a thousand sets of tiny, squeaky swings.

Squeak-squeak-squeaky-squeak-squeak…

My assessment quickly changed from “neat” to “really bloody annoying.”

And yes, my ninja skills completely failed me.

The paintings on the sliding doors were fairly intricate—and probably the reason why both photography and sketching were prohibited inside—but I was most amused by the “red-tasselled doors,” behind which bodyguards would sit in wait. If I ever build a house, I must have some installed.

One thing that struck me was the emptiness of the place. Aside from the wooden hallways, it was just full of tatami floors that were completely unfurnished beyond low tables pulled out during the day and futons pulled out at night. It started to make sense to me why Japanese society is so traditionally austere: even the madly wealthy had nothing to do.

Ginkaku-ji

I wandered over to Kyoto Park to get a glimpse of Kyoto Gosho, the imperial palace. The palace is seldom open to visitors, and given that I couldn’t see anything but sloping rooftops from outside the walls, it just ended up being a thirty-minute walk across a big open space.

It was warm enough for me to take off my jacket and a layer of clothing, though—a stark contrast to the frigid weather everyone in The Village had been so dreadfully concerned I would encounter. They don't have much perspective on "cold" there. When I was heading up to Numazu one night when there were supposed to be spots of flurries in the otherwise green mountains, a teacher asked in all seriousness if I was going to attach chains to the tires of the car.

I wanted to hit Heian Shrine, one of the half-dozen Kyoto sites that was important enough to fall under “general vocabulary” in my university Japanese classes. But the shrine was back at the south end of the park, and rather than walk straight back down again I pulled out one of my trusty maps and located something on the same latitude.

I subsequently made a 45-minute trek to Ginkaku-ji, the Silver Pavilion. On the way, I paused long enough to buy my fourth disposable camera, foolishly opting for 27 shots rather than 40 because I was starting to worry about how much it was going to cost to develop all the photos I was taking.

Unlike the area to the south of Kyoto Park, which had been filled with unflattering and ugly rusted-out buildings, the area around Ginkaku-ji was decidedly pleasant, with little shrub-lined waterways adjoining the street and prim little houses and apartments neatly arranged all the way up to the hillside. I wondered how much it cost to live there.

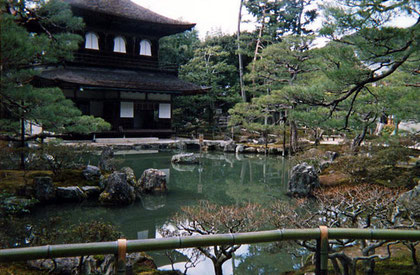

Beyond the high green hedges at the temple entrance, a man raked white sand into an intricate pattern of lines and grooves around an island-like garden of bright green. Further within I found still more elaborate patterns of raked sand around a big mountain-like cone. From across the lovely pond, the view of the simple two-story pavilion held a kind of pastoral beauty that was generally lost on the other, more overwhelming displays of wealth and power in the city. I followed a path up the side of the hill to scenes of luscious greenery that had me reaching for my camera every few seconds. To my right I could see the entirety of the temple grounds bounded by the buildings and hills of Kyoto beyond.

My general summation was, “This place wins.”

While there had once been the ambition to coat Ginkaku-ji in silver just as Kinkaku-ji is coated in gold, it was never realized. The "silver" pavilion is actually just an old brown and white cube that looks more likely to house a homeless drifter than to provide respite for a mighty shogun. I thought this only added to the charm of the place, but anyone expecting to find a shining symbol of glory is going to be sadly disappointed.

Heian Shrine

I headed vaguely south with the faith that I’d eventually hit a road I’d recognize, and surprisingly had no trouble at all finding Heian Shrine.

The shrine was built in 1895 to celebrate Kyoto’s 1100th anniversary, and is curtly dismissed in Socks’ Lonely Planet as a gaudy imitation of past architecture. But after two days of nothing but one brown timeworn building after another, the bright orange pillars and green roofs of the shrine were a refreshing infusion of colour that hinted at what all the city had looked like in its prime.

For some reason, the most immediate sight in the garden at Heian Shrine was a car from Japan’s first train; it was just sort of jammed in a corner surrounded with greenery. Dirt paths wound through various little islands of mossy green that I imagined were exceptionally beautiful when flowers were actually blooming on them. A set of big cylindrical stepping stones ran through the middle of the requisite pond, after which I came upon a rather pleasant covered bridge that gave me a sense that I’d seen whatever it was I’d paid to see.

I grudgingly noted the presence of yet another tent-covered building at the side of the pond. The expression “shūfuku-chū” (“under restoration”) has been indelibly added to my vocabulary.

A giant red torii gate straddled the exceptionally wide street to the south of the shrine, looking quite impressive above the surrounding trees and the clear, open spaces associated with a park and three museums nearby. It was a very nice area of town.