Urdaneta

Urdaneta is about four hours from Manila by bus. The Greyhound-style buses advertised air conditioning and WiFi, though the latter didn’t seem to be working very well for me. Vendors filed on to sell snacks when we stopped, which seems to be a common thing in this part of the world. I also discovered that you had to pay 5 pesos to use a rest stop toilet, which is also pretty common.

Outside Manila, the roads clear up and the Philippine countryside is green and lush. Housing generally improves, more often than not composed of cinderblocks with a variety of styles of roofing, from corrugated steel to orange tile, though some are still accented with blue tarps. On the two-lane highway, the bus never missed an opportunity to pass anything moving at a slower clip, most notably the increasingly prevalent ‘tricycle’ mini-cabs.

The moment I arrived in Urdanetta, M.’s cousin looked at my bulky hiking boots and asked to know my shoe size. Twenty minutes later, we were a block down the street in M.’s family shop when a hand reached through the window with a brand-new pair of flip-flops in my size. You don’t wear bulky shoes in the Philippines. Most people in the countryside take tricycles just to avoid walking any distance in the heat.

Santa

I recently received this forwarded mail from my mom. While it may well be apocryphal, as a firm believer that the world you get is the one you give away, regardless, I like the ethic.

The Philippines

Visiting family in the Philippines from Japan is like moving to an apartment two blocks away: Every time you go, you bring as much as you can carry. And your care package must include at least one case of seafood flavor cup noodles, of which we had two. The guy beside us at check-in had six.

You must also fill every empty space in your bags with chocolate, as this is the somewhat-acceptable alternative when every person you plan to meet assumes that all the space in your suitcase has been reserved expressly for their personal use. Our haul for family alone included a collapsible shopping cart and two sets of curtains, and our key item for next time is a garden hose. It’s not that these things don’t exist in the Philippines—the local products just don’t last as long.

On to Cardiff

The main challenge with public transport outside of London isn't that it runs off schedule, but that it runs infrequently. Every transfer point adds an average of thirty minutes to your journey. My fastest transfer was, of all places, in Bude, my last stop in Cornwall, while I had fifty-five minutes to wait in Exeter, exactly enough time to get within sight of something interesting before having to rush back to the train.

Devon County looks exactly like what romanticized upper-class pastoral life is supposed to look like. It is beautiful, lush, rolling country, and I kept waiting for someone named Mr. Darcy to appear in a carriage to offer Miss Elizabeth his gloved hand and a coat to tread upon.

Restormel & Tintagel Castles

Rather than do the sensible thing and string together coastal buses from St. Agnes to Tintagel via Padstow, I decided to hit Restormel Castle on the way.

Restormel Castle is a perfectly circular keep set within a dry moat. Little more than a thirteenth-century summer retreat, it now looks quite dilapidated as all of the valuable stones around the windows and gates have been stripped, leaving only jagged shale. It would be a brilliant to see Waiting for Godot there when it plays at the end of August.

The castle's information site bemoans itself as 'oft-overlooked,' which is exactly why I decided to swing by. As it is located roughly a 45-minute walk from Lostwithiel Station, I would recommend that it might heighten its tourist standing by placing a sign within a mile of the castle itself. Quickly finding myself surrounded by nothing but sheep and unmarked side roads, I only found the place by waving down the only biped in the area.

Four Weddings and...

Today I experienced my first Japanese funeral.

The husband of one of my fiancée’s older cousins passed away, and I was one of ten people present at the funeral.

My fiancée and I arrived first, and we spent some time waiting in the reception area of the funeral home. The staff were as polite and accommodating as always, but with almost a sense of personal embarrassment in their interaction with us. I couldn’t help but recall the traditional stigma attached to those who work with the dead in Japan—both human and animal—and wondered if these people, as hard working as any others, still suffered under the same social ignominy. Had they served in this field for generations? Or were these people new to the job, falling into the work as one falls into any other second-tier occupation?

When the family had assembled, we were called to view the body. He was placed on a high trolley with a crest on its side, laid in a simple wooden box, the lid slid back to reveal his face. The staff provided flowers for us to place around his head. It was a beautiful gesture, as if we could somehow take part in ensuring his comfort, giving us a final chance to show him some kindness, letting us feel something other than useless. I had never even known this man, but I got to feel that I had done something good for him. After a few minutes, a staff member in what seemed to be a security uniform told us it was time to go, and the lid was slid shut.

We each put a hand on the casket, ferrying him past a zen garden. This, too, was a kindness: I felt as though I were helping a friend take the next step in his journey. The guard-like man took control when we reached the destination. We followed the casket into a giant chamber with eight black doors, each marked with a gold seal, a red industrial light by its side. There were no more illusions. This was a furnace. And we were providing its fuel. Beside us were seven more doors for the same purpose. Another would be opened before we left.

We watched as the casket was slid inside and the doors were sealed. In waves of four, we took turns sprinkling tiny reddish pebbles in a cup of hot ash, each saying a prayer. We were then led to a cafeteria-like area where we were given free tea and the opportunity to order from a simple menu of drinks. The process would take roughly 45 minutes. We spoke, sombrely at first, then with greater animation. Then we were called back.

The doors were opened, and a collection of charcoal emerged on a metal table. It was collected in a broad metal pan while we waited in a room next door, where a jar was prepared. Long chopsticks were provided and then, two at a time, we each took an end of a piece of bone in our chopsticks and together placed it in the jar. The remaining pieces and dust were swept up and placed in the jar by another guard-like man, with the exception of the pieces of the skull and the topmost vertebra, which were placed inside last, resting on top. As he retrieved them, the guard-like man explained the nature of each piece—two halves of the jaw, the hard concatenations by the ears, the plates at the top of the head. We watched with curiosity, like children at a science lesson; like customers listening to a sushi chef explaining the details of his next delicacy; like we were no longer directly involved.

The jar was sealed, then placed in a plain wooden box, which was carefully wrapped in a white furoshiki (a kind of wrapping cloth used for carried goods), then hooded with a more ornate cover. The box was given to the man’s eldest son, and we were bidden farewell.

With all the guard-like uniforms, complete with hats, it felt more like going through customs than experiencing a religious ceremony. Perhaps, in a way, it was.

We took the box to the family home, where it was placed in the shrine they had prepared. A candle was lit, and each family member took turns lighting a stick of incense and ringing a bowl-shaped bell.

Freeform

Just a few little points on this one. It's been a while, and I've been out of it.

Done, Done, Done at Last!

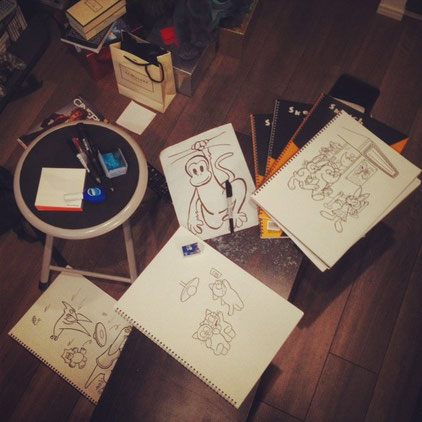

At 12:52 p.m. on February 25th, 2013, I finished coloring the last of the 112 expressions flashcards I was commissioned to make for a kindergarten in Shimo-kitazawa.

With the completion of "Do you have any pets?" I had one final task to undertake: break out my blueline pencil and markers one last time and draw a backing for each of the three remaining sets of cards.

Thoughts on a Death

|

“If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

–Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The GULAG Archipelago |

Monster Party!

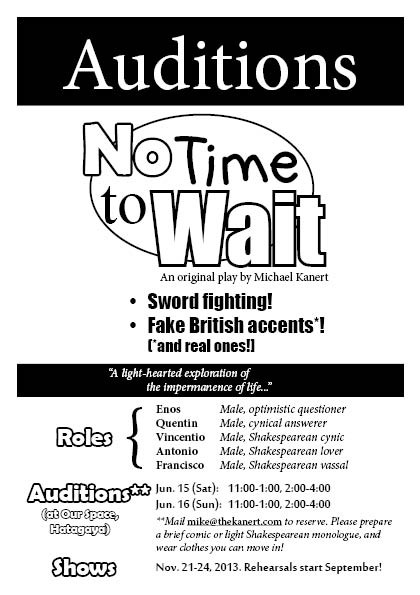

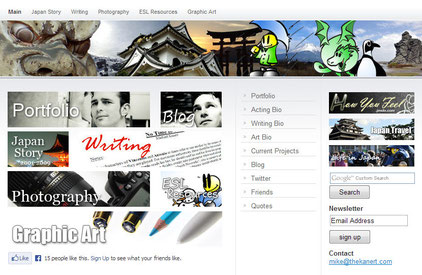

Another few days, another dozen flashcards. The Monster Party is done! I now only have Pigs & Aliens left to do (6 cards). Then I draw the backings, and I will finally be free to try to get Fragile Order and some poetry published, and look into getting No Time to Wait produced in Tokyo. Then, of course, there's producing Jonny Barefoot's new album along with my friend Laurier and working with my friend Rodger to finally get Unremarkable in a newspaper.

I very often think I need to quit my paying job so I can do all the non-paying jobs I do...

No Exit is Done!

No Exit is done! For those who missed it, this is what it looked like! Photos by Mike Kanert, Wendell T. Harrison and Juna Hewitt.

Two More Themes

No Exit opens in 2.5 hours! In the meantime, I have 2 more themes done from my flashcard set. Just 17 cards left! (Just...)

Hardest Sets Done

As of this afternoon, the hardest sets are done. This leaves 29 cards left to color, with 55 knocked out. The Knights set was a challenge because I wanted to achieve a sort of stained glass effect. I'm quite happy with the results. They look a little fuzzy at certain resolutions on the screen, but print just fine.

40 Down

In the coloring process. Of the 84 drawings I had left unfinished, 40 have been completed.

I've been going by themes. I started with my "Rabbit & Rhino" and "Baby Bear" sets, which are now complete. I had no idea there were 40 of them. (The hamsters and kittens are sub-sets of the Rabbit & Rhino theme.)

It's amazing how much you learn when you produce on a mass scale. Just drawing these 40 I taught myself new background and lighting techniques that I hadn't even figured out doing the original 28 flashcards last year. I feel much more confident in my work, and in my ability to produce output that is of increasingly consistent quality. I've also learned a few good techniques for turning "Ho-hum" into "Wow!"

Heh... I'm even getting closer to being off-book for No Exit. Just three weeks away! (Yikes!!)