Emperor Nintoku’s Tomb

The largest burial mound in the world

The Kofun Period (250-538 CE) was the third period of human history in Japan, following the Jomon (14,000-400 BCE) and Yayoi (400 BCE-250 CE) Periods. During this time, colossal tomb-mounds called kofun were constructed for Japanese nobles, members of the imperial family, and powerful members of the central government, thus giving the period its name.

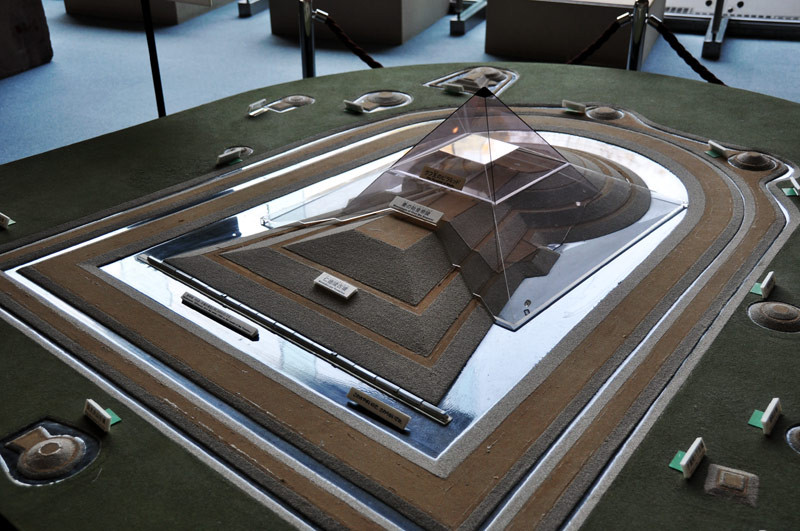

While several styles of kofun existed, the most impressive consisted of a terraced cone abutted by a long trapezoidal platform, giving these tombs the aerial profile of a traditional keyhole. The largest kofun, or tumulus, is Daisen-ryo, built in the early 5th century for Emperor Nintoku, the 16th emperor of Japan.

Nintoku’s expansive keyhole tomb lies in what is now Sakai City in the southern part of Osaka Prefecture. Covering an area of 32 hectares (79 acres), Daisen-ryo is the largest burial mound in the world, estimated to have taken 16 years and 6.8 million man-days of labor to complete, and is said to contain a greater volume of material than the Great Pyramid of Giza. At 486 m (1594 ft) in length, the mound is in fact twice as long as the base of the Great Pyramid, though at 35 m (115 ft) tall, it is only about one-quarter the height.

The tumulus is surrounded by three moats, the soil from which was used to build the mound itself. When it was constructed, the kofun’s three-tiered slopes were covered with stone and grass, with small terracotta figures, called haniwa, lining each terrace, while platforms for religious ceremonies called tsukuridashi were built on either side of the narrowest part of the tomb.

In an attempt to reduce erosion and weather damage, natural forestation has been allowed to take place on the tomb over the last century, and now the kofun’s entire 2.7-km (1.7 mile) perimeter is surrounded by a dense forest breached at only a single point, where visitors may approach no further than the near end of a bridge placed across the second moat. The ancient emperor’s tomb is announced by a single small torii gate standing at the terminus of a carefully-raked gravel path, beyond which the burial mound peeks out in the guise of a forested hillside.

Nobody is supposed to have crossed the inner moat since a typhoon in 1872 damaged the front of the tumulus, leading to the discovery of a large stone coffin, glass tableware, and gold and copper swords and armor. The Boston Museum of Arts still holds artifacts said to have been excavated from the site. However, the rear conical mound has never been opened, and given certain inconsistencies in the historical record, historians are skeptical as to whether its occupant is actually Emperor Nintoku and not some other ancient ruler.

At its height, kofun tradition spread across all of western Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku, even approaching the site of modern-day Tokyo, with prominent examples still in existence in Nara and Miyazaki Prefectures. However, the sixth century saw a gradual decline in kofun construction, and by the seventh century the growing influence of Buddhism over the Yamato court led to the abandonment of large mounds honoring the dead, with rulers electing instead to construct opulent cities and temples to express their authority.

Daisen-ryo is surrounded by a total of twelve subordinate tombs, both large and small, some of which lie directly across the street within the bounds of Daisen Park. To look at them now, many of these ancient monuments are no more than a wide bump in the ground or an ill-kempt marshy island, and without their descriptive plaques, a visitor might not even know they were there.

Daisen Park also houses the Sakai City Museum, where visitors can find a reasonable collection of local artifacts, including haniwa and pottery excavated from nearby tumuli, in addition to a variety of displays illustrating the region’s development into a prosperous port city in the Middle Ages. The park and kofun are both a 10-minute walk west of Mozu station on the JR Hanwa line (32 minutes from Osaka if you catch the airport express and change at Mikunigaoka, ¥360). Museum entrance is a reasonable ¥200.

Daisen-ryo is not to be visited for the view. There is, in essence, nothing to be seen, and the tomb is now most prominently used as a perimeter around which to jog. But the sense of being in the presence of something so old, illustrating both the indelible longevity of power and the humility impressed upon it by time, resonates with a depth beyond anything that can be captured by the eyes.

Also in the Area

Published June 2010. Museum photo and ground view of Daisen-ryo © 2010 Michael Kanert. Aerial photo from National Land Image Information (Color Aerial Photography), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, 1985.